Herein, I propose a timeline that is capable of supporting three main scriptural passages that surround and “contain” the time of slavery experienced by the Israelites in Egypt. I understand fully that this proposition runs afoul of accepted traditions – most of which consider only one of the passages at a time. I also understand that the two key manuscript problems have historically been resolved differently than I have attempted to resolve them. However, this timeline fits all three passages (Genesis 15, Exodus 12, and Galatians 3) simultaneously.

The specifics are provided immediately below. This is followed by a description of the analysis used, and then by a recapitulation of these specifics.

-

The Hebrews use a lunar calendar. Abib means “spring.” It is usually pronounced Aviv. This is the month that begins with the new moon that precedes the vernal equinox. Abib 15 would occur the day after the full moon. See Exodus 12 for the significance of this date.

Abram arrived in Canaan on a specific day (arguably Abib 15) some years after God’s original commission. This began the Exodus 12 time clock. Soon afterwards, Abram arrived in Shechem.

- With that begins with the new moon that precedes the vernal equinox. Abib 15 would occur the day after the full moon. See Exodus 12 for the significance of this date.

- God soon spoke to Abram again with promises, and the Galatians 3 time clock began. This occurred two or three months after he arrived in Shechem. He then built an altar there.

- A few years later, God spoke to Abram (Genesis 15:2-16) about the 400-year period that was still to come.

- Twenty five years after the arrival of Abram in Canaan, Isaac was born to Abraham and Sarah.

- Five years after that (30 years after the arrival in Canaan) Abraham held a special ceremony to mark the weaning of Isaac. This event starts the 400-year Genesis 15 time clock. It was then 30 years after the arrival of Abram in Canaan, which had started the time clocks for the Exodus 12 and Galatians 3 passages.

- One hundred seventy-five years later Isaac died, and Joseph was released from prison in Egypt to become the “prime minister.”

- Nine or ten years later, the other sons of Jacob moved Jacob to Egypt. This is about 185 years after the weaning of Isaac. There were about 215 years left on all three time clocks. Kohath, second son of Levi, was already born before that.

- Joseph died about 70 years later. There were then about 145 years left on the three time clocks.

- Levi died about 20 years after the death of Joseph. This left about 125 years on the three time clocks.

- After some number of years things began to get ugly in Egypt. This happened after the time of Joseph was forgotten (Exodus 1:8).

- The period of slavery and oppression happened at some point in the remaining 125 years.

- Moses was born about 45 years after Levi died. The slavery was already under way by then. Eighty years remained on the three time clocks.

- It is possible (but not likely) that the slavery actually commenced after Aaron was born (three years earlier than Moses).

- Herewith the proposition is posited that the period of slavery in Egypt lasted between 80 and 100 years. This provides at least 25 years in which Joseph and his brothers could be “forgotten.” One hundred years is arbitrary, but it was not more than 125 years.

- On Abib 15, exactly 430 years after Abram crossed the Jordan into Canaan, Moses led his descendants out of Egypt with great wealth. The Genesis 15 and Exodus 12 time clocks expired.

- Two or three months later, still in the same year of the departure, God spoke the Decalogue to the Israelites assembled at the foot of Mt. Sinai. The Galatians 3 time clock expired.

Analysis

There are three key scriptural passages that can be used to unravel the mystery of the Israelite “visit” to Egypt. They are: (1) the prophetic passage in Genesis 15, (2) the account of the departure from Egypt in Exodus12, and (3) Paul’s discussion of the distinction between the promise and the law in Galatians 3. A few other passages can be used to support the analysis, but these are the main ones. In particular, Genesis 12 is found to be useful.

Before we conduct the analysis, there are two key textual issues that need to be addressed. The first of these occurs in the Genesis passage. The second occurs in the Exodus passage. Our efforts will not eradicate the issues, only help us to understand what they are. While the isolated issues cannot be definitively resolved, a sort of “cross-analysis” can emerge. Said “cross-analysis” can reasonably reconcile the first two passages when considering them as though they were components of a single narrative. This we shall do. The third passage presents a different, but parallel, concern and can be reconciled to the other two. In so doing, we will gain a clearer understanding of this key period in the development of the natural descendants of Abraham.

1: PROPHECY OF OFFSPRING: GENESIS 15

Let’s begin by considering each passage in isolation and highlighting certain aspects of them that matter to us.

12 As the sun was setting, Abram fell into a deep sleep, and a thick and dreadful darkness came over him. 13 Then the Lord said to him, “Know for certain that (for) four hundred years your descendants will be strangers in a country not their own and that they will be enslaved and mistreated there. 14 But I will punish the nation they serve as slaves, and afterward they will come out with great possessions. 15 You, however, will go to your ancestors in peace and be buried at a good old age. 16 In the fourth generation your descendants will come back here, for the sin of the Amorites has not yet reached its full measure.” (Genesis 15:12-16, NIV, underlines and parenthesis added by the author)

The four key facts in this passage are:

- Descendants would arrive,

- Enslavement and mistreatment in a foreign land was in the future of the descendants for some period of time,

- Departure from the foreign land would occur in the fourth generation after the migration to said land, and

- A 400-year period of time was involved.

“Four Hundred Years”

One of the most common interpretative problems we have with this passage is the tendency to totally conflate the first three key facts. In essence, we usually interpret the passage to say the “enslavement and mistreatment” lasted for 400 years and affected all the generations of the descendants of Abraham. That is not, in fact, what the passage says. The passage seems to state that the period of the emigration would last for 400 years. (We shall discuss whether that was likely the case.) Within that 400-year period, the emigrants would experience some unspecified period of “enslavement and mistreatment.” That period of “enslavement and mistreatment” might last from only a very brief time up to most of the 400 years. That is not specified in the passage. We shall see that even this interpretation is not likely to be accurate.

Let’s conduct a bit of analysis that might be useful in understanding the passage. After all, any of our English translations of the narrative are just that: they are translations from Hebrew to English. Each is therefore colored by the understanding of the translators. Other understandings may be just as accurate.

In the passage, God Himself is prophesying to Abram within the context of a very solemn occasion. God is the final arbiter of the events which He was describing to Abram that evening. He made sure Abram understood the certainty of the coming events. In light of His authority, no power could prevent that which was to occur. Understanding the scope of the passage is, therefore, potentially important to us. The components are re-stated here to increase our grasp of their content.

First, it was absolutely certain that Abram would produce descendants and that some descendants would leave Canaan at some point in time. Upon leaving they would go to some other country. Upon arrival in that other country, they would remain there for a period of many years (perhaps 400 years, but that is discussed below). Abram himself would not make that move: it would be made by unspecified descendants of his. That is, the identities of the relevant descendants were not specified. Would it be the very next generation, not yet born? Or would the emigration begin many generations later? These facts were not made plain at all.

God also made clear that during the 400-year period of His prophecy, the not-yet-specified descendants would experience the enslavement and mistreatment. He did not say when that would begin. He did not say how long it would last. He simply said it would happen without any information as to start, end or duration of the times of trouble. It might, or might not, start immediately upon their arrival in the foreign land.

At some point in time after that period of troubles began, the descendants would leave that foreign country with considerable wealth. Some while before their departure, judgment would be meted out to the “host” nation. So the descendants of Abraham would be reduced to slavery at some future point in time but then be released with great wealth. Both changes happened suddenly, not gradually.

Four Generations

Next, God specified that the return would occur in the fourth generation from the generation that migrated to the foreign country. The following sequence is implied.

- Emigrant generation – Canaan to “somewhere”

- Second generation – still “somewhere” (most were born before migration)

- Third generation – still “somewhere”

- Returning generation – “somewhere” to Canaan

This simple presentation actually gives rise to another problem. The first generation would have had to be born before they could emigrate. Furthermore, the returning generation would not yet be dead at the time of their departure from Egypt. It turns out that most of the second generation was born before the migration occurred. A 400-year duration for these things implies generations that lasted well in excess of 100 years each – not likely. Four hundred years is a fairly long time period, the duration of which simply implies more than four generations. How can this be? Let’s go a bit deeper.

Simply put, the 400-year period of time would seem to require more than four generations. While a generation is a hard thing to define in terms of time duration, no one would propose that generations last in excess of 100 years each. The most reasonable resolution is that more than four generations would be involved. In that case, there must be a distinction between the four generations in the prophesied sojourn and the generations who “inhabited” the 400 years. In that case, the 400 years and the four generations are not an exact match. We can provisionally propose that this means there were more than four generations to be involved but only four in the foreign land. It might take several more generations to fill the 400 years, but the fourth-generation aspect of the prophecy is quite precise. So let’s separate the two ideas and consider evidence that might apply to each.

We, with the advantage of hindsight, know the destination of the emigration of the descendants of Abraham. It was Egypt. We also know enough of the genealogy of his descendants to be able to trace some of the families through the period up to the departure (exodus) from the place of exile. So let’s gather up that evidence.

Levi to Moses

First is the genealogy of the descendants of Abraham. The following list traces that genealogy specifically from Abraham to Moses. Moses was the most significant character of his generation and the direct genealogical evidence is easy to find (Exodus 6:14-26).

Abraham

Isaac – first descendant

Jacob – migrated

Levi – migrated

Kohath – migrated as a child

Amram – born in Egypt

Moses – born in Egypt; definitely born into slavery; leader of the departure

First, it is obvious there are six generations after Abraham in this list, not four. So, can God not count? How could these data fit the “fourth generation” aspect of the prophecy? Let’s force the four-generation idea and see what might fall out. If we do that using Isaac as the starting point, then the fourth generation in that line would be Kohath. Kohath did not outlive the sojourn, so he cannot be the end point.

But, if we start from Moses and work backward, what happens? We know that Moses did leave Egypt. So, if we count backward using Moses as number one, who is number four? That person is Levi. Does that make sense to us? Yes, Levi emigrated to Egypt with his father, his brothers and his sons. Even more importantly, the emigration began with his younger brother, Joseph, more than twenty years earlier. Put another way, Joseph was the first emigrant, even though he was a prisoner when it happened. If we accept the idea that Joseph and his brothers, including Levi, are the “first” generation of the prophecy, then their great-grandsons would be in the fourth generation. (This is an imprecise device because some may delay fathering and others may father at young ages.) If, however, we use Moses as the endpoint, we get to the “fourth generation” of the prophecy. Moses is the fourth generation in his specific genealogical line coming down from Abraham if we accept that Levi and brothers were the first generation. This omits Isaac and Jacob from consideration because they preceded the “first” generation.

We can understand why we might omit Isaac in the counting of generations because he never set foot in Egypt. However, Jacob did go to Egypt with his sons. So, why would he not be the first generation in Egypt? Simply put, he was not the first to make the emigration – Joseph was. Joseph got to Egypt over twenty years before the rest of the family. Furthermore, the contract made by Pharaoh was with Jacob’s sons, not with Jacob (Genesis 47:5-7). If Joseph is first, then we propose his generation was the first of the four. Thus, Jacob, even though older, can also be omitted from the counting, just as Isaac was. This, then, is a plausible perspective of the “fourth generation” aspect of the prophecy. But what about the 400 years?

“Offspring”

We have already established a plausible explanation for the “fourth generation” term used in the prophecy. We have also established that “four hundred years” and “fourth generation” are very difficult to reconcile with one another. To get at that let’s go to the first item on our list of prophetic elements – descendants. Isaac was the first descendant of Abraham. He was not, by our current proposition, one of the four generations. His lifetime does matter however. The question we have before us involves a specific duration of things in terms of time. If it is not feasible to start counting time when the first Israelite (Joseph) entered Egypt, is it useful to start reckoning time within the context of the life of Isaac? After all, that gives us two more generations to push time out toward 400 years.

If we use the life of Isaac as a starter for the 400 years, at what point shall we start the reckoning? A reasonable point would be his birth. Other than his death, there is only one other point in time that would contribute to an understanding of the impact of his life on the passage of years, and we will hold off on discussing that point for now. So, if we begin our reckoning with the birth of Isaac, can it be that 400 years could pass before the exodus? Let’s construct a table of life durations for these generations.

TENTATIVE CHRONOLOGY

Abraham – lived 175 years; Isaac was born when he was 100

Isaac – lived 180 years; Jacob was born when he was 60

Jacob – lived 147 years; Levi was born when he was about 80

Levi – lived 137 years; Kohath was born before he was about 47 (the time of migration to Egypt)

Kohath – lived 133 years; no information when his sons were born

Amram – lived 137 years; no information on when his sons were born

Moses – lived 120 years; led the return at age 80

The short answer is, Yes, it is feasible to fit the 400 years into the cumulative lives of these generations of Abraham and his descendants. It can be shown that from Isaac’s birth to the emigration that included Levi was about 190 years. (Joseph had arrived about 23 years earlier.) For the moment, let’s continue to assume, that Isaac’s birth started the 400-year time clock. The arrival of Levi in Egypt would then be 210 years before the exodus. Levi, it can be shown, lived about 89 years after the migration and he was never a slave. The total period from the birth of Isaac to the death of Levi was about 279 years. There remained yet 121 years until the exodus after Levi’s death, and he was never enslaved. (The year totals used in this section are not exactly congruent with our total paradigm because there are matters that are not included at this point. This section is for illustration and comparison only.)

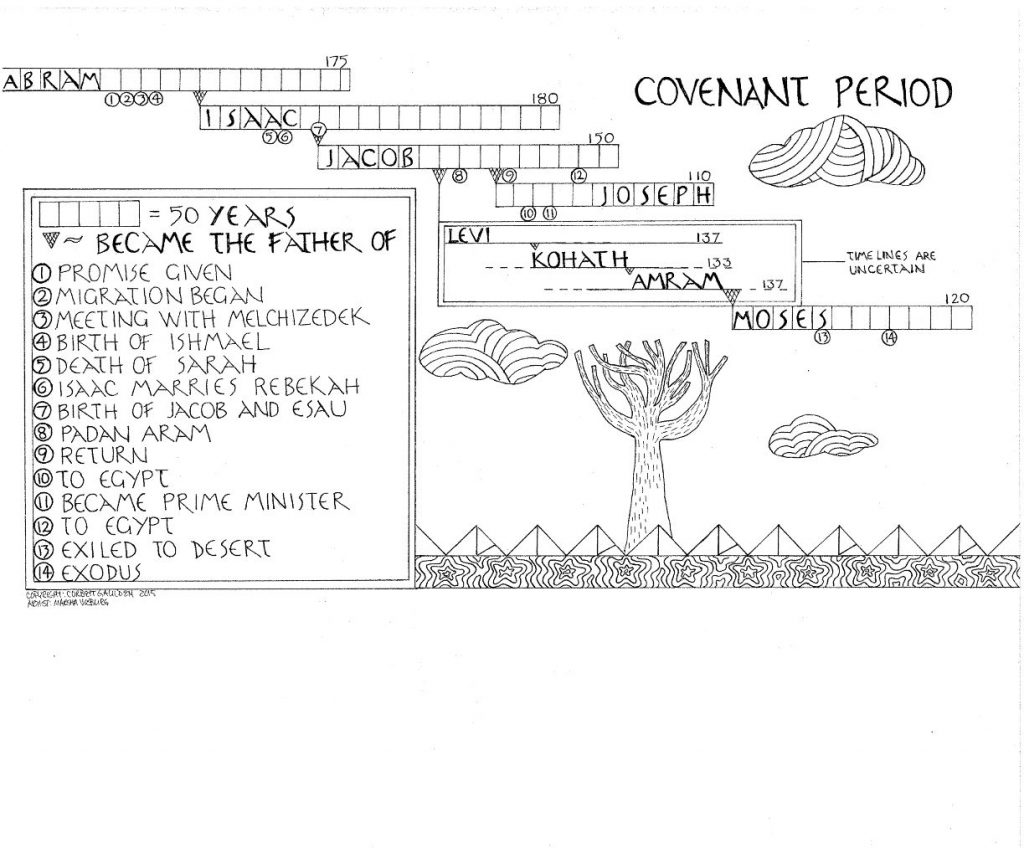

Click the below image to see an enlarged graphical depiction of the Covenant Period:

We don’t know when the period of enslavement began by the way, but we know it lasted more than 80 years because that is how old Moses was when he led the departure from Egypt, and he was born into slavery. At this point, in this analysis, the period of enslavement lasted between 80 and 120 years. This goes against our traditions, but it is consistent with the 400-year period of the prophecy. The text, though, states the slavery lasted 400 years – or does it?

The Assumed Preposition

Most English language translations of the Bible state, or at least strongly imply, a 400-year enslavement. However, if we resort to the Hebrew text, this is not necessarily the case. The crux of the matter is that the text does not contain any preposition (“for” or otherwise) before the term “four hundred years.” The preposition is assumed by translators. Suppose for a minute, though, that the 400 years refers to some other time reckoning. Suppose it begins with the first descendant, Isaac. That was the proposal we examined in the previous section.

In fact, the words translated “(for) four hundred years” occur after the phrase into which they are typically inserted. A better rendering would be: “your descendants will be strangers in a country not their own, and they will be enslaved and mistreated there (for) four hundred years.” If we remove the (for) from the phrase, the 400 years may refer to anything. Because “for” is not present in the Hebrew, nor is any other preposition, the ramifications of this might be important to us.

We may, for the moment, infer that the statement could be paraphrased to read something like the following:

“You will surely have descendants. At least some of those descendants will migrate to another country. At some point in time, while they are in that country, they will be enslaved and mistreated. In the fourth generation after they migrate into that country, they will leave and will be wealthy when they do so. A period of four hundred years will be somehow involved in this.”

The 400-year period remains in place and remains somewhat ambiguous. However, in this construction, we have fit all the required history. Every element will fit except our tendency to assume the 400 years of slavery. At this point of the analysis though, we don’t even know what the 400 years is referring to.

2: IN EGYPT*: EXODUS 12

Now the length of time the Israelite people lived in Egypt* was 430 years. At the end of the 430 years, to the very day, all the Lord’s divisions left Egypt. (Exodus 12:40-41, NIV)

So, Where were they?

*The usual Hebrew text, the Masoretic, says “Egypt” here but a note appears in that spot to inform the reader that the Samaritan Pentateuch says “Canaan and Egypt” and the Septuagint says “Egypt and Canaan.”

There are two things we might want to notice in analyzing this passage. First, 400 years and 430 years are not the same thing. *Second, in nearly every translation, the word “Egypt” in verse 40 has some sort of note attached to it. The reason is that two well-known versions of the scripture have additional information in that spot. The Samaritan Pentateuch reads “Canaan and Egypt” where most modern translations have only “Egypt.” At the same time, the Greek Septuagint reads “Egypt and Canaan” in the same place. The standard Hebrew sources present us only with Egypt, but these other sources diverge from that.

Here is our problem. If we use the typically-used Hebrew versions, we have a 430-year period that even ends on a precise date (the 15th of the month Abib). But the 30-year difference in this timeframe and the Genesis 15 timeframe is too big to ignore. In the Genesis passage, God prophesies a 400-year period. We cannot discount that. In the Exodus passage we have a very precise statement concerning the 430-year period. Superficially, they seem to refer to the same phenomenon. Certainly they seem to end at the same time – the time of leaving Egypt.

If Egypt is the only land actually referenced, and if the two referenced time periods end simultaneously, we are left with two possibilities. Either they do not start at the same time, or one of the two numbers is in error. These things cannot simultaneously be true. So, let’s apply our analytical approach.

- The descendants (however defined) lived in Egypt* for 430 years.

- It was 430 years to the day, from some specific time, that they left Egypt.

Our best hope for unraveling the apparent contradiction is to consider the manuscript divergence as a possible solution. The two phrases, “Canaan and Egypt” and “Egypt and Canaan” appear to be equivalent. They differ only in the placement of the two place-names in relation to one another. If we do not require them to refer to sequence, but only to total duration of two periods of history that are adjacent to one another, things will work out okay.

Because the 430-year period ends with the Israelites departing from Egypt, we can proceed with assumptions that look like this.

- At some previous, specific point in time, the Exodus writer began counting the time that eventually yielded the 430 year result, precisely.

- The 400 hundred year period of Genesis 15 began at a time that was 30 years later than the time being reckoned by the Exodus data.

- The end points are identical.

Alternatively,

- The time considered important in the Exodus narrative commenced.

- Thirty years later, the time prophesied by God in Genesis commenced.

- The two time periods ended simultaneously.

The Thirty-Year Gap

So what happened during the 30 years between the two starting points? That is really the heart of the reconciliation between the two. Did anything significant happen during that time? Does that matter to our understanding of the narrative?

The real question here relates to being able to isolate the 30 years in Genesis that fell between the start of reckoning in Exodus and the beginning of the 400 years God prophesied to Abram in Genesis. This will not resolve every problem, but it may enable us to reconcile the way the two time periods related to one another. Of course, we cannot know everything that transpired in the mysterious 30-year period, but if we can discover beginning and ending points, we can understand the place in the narrative that the thirty year period holds.

Let’s use the 400-year timeframe of Genesis 15 as the anchor for the discussion. If we can successfully “superpose” the 430-year time period over the 400-year time period, so that the two have the same ending point, we have the ability to see whether the 30-year period makes any sense when compared to the biblical narrative.

In essence, the Exodus time clock began 30 years earlier than the time clock of the Genesis prophecy. That presents no contradiction, just an interesting juxtaposition, and that is what we wish to isolate.

In the previous section on the prophecy of Genesis 15, we suggested that a proper fit for the material might be to begin it with the birth of Isaac and end it with the departure from Egypt. There are some remaining issues when we do that, but it fits the timeframe fairly well. So, if we use that as our point of departure, the question is, did something significant to the patriarchal narrative happen 30 years before Isaac’s birth? Herein we propose the answer is “Yes.” About thirty years before Isaac was born, Abram and God were having some serious interactions. However this is not the 30-year period of interest. Twenty five years before Isaac was born, Abram arrived in Canaan, and the specific promise of offspring was made.

3: PROMISE BEFORE THE LAW: GALATIANS 3

For an unrelated reason, Paul, in the letter to the Galatians, mentions this same period in history.

“What I mean is this: The law, introduced 430 years later, does not set aside the covenant previously established by God and thus do away with the promise.” (Galatians 3:17, NIV)

When Paul wrote these words, he was not engaged in some sort of historical analysis such as the one we are engaged in. However, we may safely assume that he knew whereof he spoke. On some basis, it was known to him that God’s promise to Abram was made about 430 years before the law was given. We know that the law was given at Mount Sinai after the Israelites departed from Egypt. Reasonably careful analysis of the Exodus text will reveal that the Sinai events commenced shortly after the departure from Egypt – probably within about two or three months. In the context of a 400-year stretch of history, two months is not a very long period.

So, for the sake of argument let’s say the 430 years in this passage is virtually the same as the 430 years in the Exodus 12 passage since they end at about the same time. Will this “match up” with the data in Exodus? If the endpoint of the two referenced passages is the same, and the two periods of time are of the same duration, then the two periods overlay one another quite well. That is, the two time periods have almost identical starting points, and almost identical ending points. Whatever the chronicler in Exodus was referring to as the beginning of his reckoning was almost the same as the starting point of the time Paul was speaking of in Galatians.

Looking at this another way, we can say that the point in time at which the people began the 430 years in Egypt (and Canaan) was about the same point in time at which Abram received the promise. It is also true that the point of time at which the Israelites left Egypt was about the same point in time the law was given at Sinai. Since the second proposition is arguably accurate, then the first proposition is also arguably accurate.

Let’s put a bit of flesh on this outline. Abram arrived in Canaan at some point in time. He quickly arrived in an area called Shechem. When he got there, God spoke to him on this wise: “To your offspring I will give this land.” (Genesis 12:7). Previously, God had instructed Abram to move and had implied He would provide offspring (Genesis 12:2). At the point of his arrival in the land, He explicitly promised offspring. This is the promise Paul spoke of in Galatians 3. It cannot be another. From that time at Shechem, 430 years passed and the Israelites left Egypt headed for Canaan. When they arrived at Sinai, they received the law. During that time, they lived in “Canaan and Egypt,” which is consistent with the Exodus 12 passage in some manuscripts such as the Septuagint. If these manuscripts preserve this information best, then this matches. (It is true that Jacob was out of the country for about 20 years, but at that time, Isaac was still the keeper of the promise.)

We have just concluded a persuasive argument that the time periods described in Exodus 12 and Galatians 3 are virtually the same. They superpose one another almost perfectly. The arrival in Canaan and the giving of the promise happened at almost the same time. The departure from Egypt and the giving of the law happened at almost the same time. In other words, the two passages refer to the same time period with very slight differences at the ends. Do they both match up with the Genesis 15 passage?

The Thirty Years – Again

In short, Yes, they do. The Genesis 15 passage ends at the same point in time as the Exodus 12 passage. Therefore, the congruence with the Galatians 3 passage is about the same as to endpoint. This suggests the Genesis 15 passage indicated a starting point 30 years after the starting point of both the Exodus 12 and the Galatians 3 passages.

- God instructed Abram to leave everything and migrate to some other place, implying offspring.

- Abram arrived in Canaan (the other place) at some point in time.

- Very soon thereafter, God made the promise of offspring to Abram.

- If Isaac was born thirty years after the promise was made, this will start the Genesis 12 clock. (It was only 25 years before Isaac was born. This is explained below. The numbers will be off slightly until all factors are considered.)

- Arguably, the departure from Egypt occurred 400 years after Isaac (offspring) was born. (Further analysis comes later. His birth did not begin the counting.)

- This occurred the same day as the end of the Exodus 12 passage.

- The giving of the law occurred a short time later (far less than a year later).

About the only thing left to do is to analyze the time of birth of Isaac relative to these passages. Is it feasible that Isaac’s birth happened about 30 years after the arrival of Abram in Canaan? Yes, it is feasible, but not accurate, as we shall see. However, there are two antecedent considerations.

God is a careful observer of important things. He Himself was to be the first patriarch, the Prime Patriarch, of the nation He was forming from Abram. As the Patriarch, it seems it was necessary in the mind of God that He should have His own son involved in the matter. Abram was His selection as the son for this purpose. However, Abram already had a father. His father’s name was Terah. At a certain point in time, God gave to Abram the following instructions:

The Lord had said to Abram, “Leave your country, your people and your father’s household and go to the land I will show you.” (Genesis 12:1)

Abram was to leave a lot of things, all of which contributed to his identity and wellbeing. He was not asked to leave his father, only his father’s household. This may not seem an important distinction, but it is. One of the stark implications is that Abram left only after Terah was dead. Because Terah was deceased in this scenario, God was not violating Terah’s fatherhood by adopting Abram. Once Terah had died, Abram was “available” for adoption. Furthermore, it is clear that Abram was 75 years old when he set out (Genesis 12:4) to go to Canaan. The journey probably lasted two or three weeks, not much longer anyway. These inferences work well if Terah was about 165 years old at the time Abram was born. That works very nicely with the overlap of the lives of Abram and Eber.

The second antecedent is that God “had said to Abram” in the passage. It does not say that God “said to Abram.” The difference in tense (had said versus said) implies that Genesis 12:1 refers to some indefinite point in time before Abram actually departed from his home for the new country. It might have been several years.

One final fact gets in the way at this point. Abram arrived in Canaan at about age 75. Twenty five years later Isaac was born, when Abraham was 100 years old. If we start the 430 years at the birth of Isaac, then Abram would be 70 years old at that time, not 75. Making this more difficult is the fact that the Exodus passage is so precise – down to the day. The “day,” as a result of our analysis so far, was a specific time of some arrival of somebody somewhere. Abram arrived when he was 75 though.

This analysis has reconciled everything in the three key passages to a period of time within five years. That is remarkable for such ancient events, but we are still off by five years in this reckoning. Once again, let’s gather the relevant data we have so far examined.

- God told Abram to go somewhere and implied offspring.

- At some later time Abram complied and arrived in Canaan after a little while. The arrival was on a specific date, perhaps Abib 15 of that year.

- Twenty five years later Isaac was born.

- Isaac’s grandson, Joseph, arrived in Egypt one hundred sixty two years later.

- Isaac died in Canaan thirteen years after that (when Joseph was thirty; inferred).

- Jacob’s sons (and grandsons), and Jacob arrived in Egypt about 23 years after Joseph and about nine or ten years after the death of Isaac.

- In the fourth generation after that, Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt at God’s behest.

Weaning Day

Can we reconcile the 25 years between Abram’s arrival and Isaac’s birth with the 30 years we need to make this timeline work? How can we do so?

It turns out there is a condition under which that can be done. There may be others, but there is one for sure that fits the scripture quite well. If we begin the reckoning of the 400 years of Genesis 15 with the ceremonial weaning of Isaac, and if that weaning ceremony occurred when Isaac was five years old, it all comes together. It is clear from scripture that Abraham prepared for a great ceremony to mark the weaning of Isaac (Genesis 21:8). This ceremony was of vital importance because it, in some sense, solidified the inheritance of Isaac. It would mark the time when he began to be educated as the son of the chief man. No longer would he be the darling who ran about the camp getting into things. He would be the heir. To the mind of Abraham, he would be the official heir and all the camp would know that. This could very likely be the source of the ire of Hagar and Ishmael that led to their banishment. Until that ceremony there might have been some hope Ishmael would be the heir, but the ceremony would officially end that hope and all the camp, as well as the friends of Abraham, would know who the headman was to be from that time on.

In short, on the day of the “weaning ceremony”, Isaac would come into the fullness of the carrier of the identity of “descendant of Abraham.” Some will worry about his being five years old before he was weaned. Why not much earlier, they may say? Why would it have to be earlier? There is no reason for any particular age to be the age of weaning. The wet nurses in the camp could sustain the heir for many years. Rather it is likely that Abraham would determine the ceremony in advance to announce and formalize this stage in the development of his son, and that weaning was basically a metaphor for the event.

This means the 400-year time clock can be adjusted to begin with the ceremony for Isaac. This five year adjustment will make everything else line up quite well. In essence, the five years would be “made up” during the time after the death of Levi and the other sons of Jacob and before the birth of Moses.

SCRIPTURAL CONVERGENCE

Now, we can fully reconcile all these portions of scripture with a very feasible explanation. It goes like this”

- Abram arrived in Canaan on a specific day (arguably Abib 15) some years after God’s original commission. This began the Exodus 12 time clock. Soon Abram arrived in Shechem.

- God soon spoke to Abram again with promises, and the Galatians 3 time clock began. This occurred two or three months after he arrived in Shechem.

- A few years later, God spoke to Abram (Genesis 15:2-16) about the 400-year period that was still to come.

- Twenty five years after the arrival of Abram in Canaan, Isaac was born to Abraham and Sarah.

- Five years after that (30 years after the arrival in Canaan) Abraham held a special ceremony to mark the weaning of Isaac. This event starts the 400-year Genesis 15 time clock. It was then, 30 years after the arrival of Abram in Canaan, which had started the time clocks for the Exodus 12 and Galatians 3 passages. Possibly, this happened on Abib 15.

- One hundred seventy-five years later Isaac died, and Joseph was released from prison in Egypt to become the “prime minister.”

- Nine or ten years later, the other sons of Jacob moved Jacob to Egypt. This is about 185 years after the weaning of Isaac. There were about 215 years left on all three time clocks. Kohath, second son of Levi, was already born before that.

- Joseph died about 70 years later. There were then about 145 years left on the three time clocks.

- Levi died about 20 years after the death of Joseph. This left about 125 years on the three time clocks.

- After some number of years things began to get ugly in Egypt. This happened after the time of Joseph was forgotten (Exodus 1:8).

- The period of slavery and oppression happened at some point in the remaining 125 years.

- Moses was born about 45 years after Levi died. The slavery was already under way by then. Eighty years remained on the three time clocks.

- It is possible (but not likely) that the slavery actually commenced after Aaron was born (three years earlier than Moses).

- Herewith the proposition is posited that the period of slavery in Egypt lasted between 80 and 100 years. This provides at least 25 years in which Joseph and his brothers could be “forgotten.” One hundred years is arbitrary, but it was not more than 125 years.

- On Abib 15, exactly 430 years after Abram crossed the Jordan into Canaan, Moses led his descendants (the Israelites) out of Egypt with great wealth. The Genesis 15 and Exodus 12 time clocks expired.

- Two or three months later, still in the same year of the departure, God spoke the Decalogue to the Israelites assembled at the foot of Mt. Sinai. The Galatians 3 time clock expired.

This proposed history offends our traditional interpretation of these events to some extent, particularly as regards the period of slavery. It is, however, entirely consistent with the biblical narrative. Furthermore, it reconciles three very important understandings related to the period of the patriarchs. Within the assumptions explained herein, all three passages are completely accommodated.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.