You can call him a Damascene if you wish. That would be just fine. He was an Aramean, and thus not a Canaanite. That could be important. The Canaanites were descended from Ham, whereas the Arameans (we would call them Syrians these days) were descended from Shem. In fact, they were closely akin to Abraham. There is some slight possibility that Eliezer was a displaced Canaanite who happened to come from Damascus, but that does not seem a reasonable conclusion. We are not entirely certain of the facts but it seems best to make the following assertion. Eliezer was an Aramean from the city (or area) of Damascus who had attached himself to Abram. This probably occurred even before Abram relocated to Canaan. One could assume that all the servants of Abram that came into his care after the migration were either Canaanites or Egyptians. Those in his employ before the migration were probably Semitic persons, like Eliezer.

Servanthood came in a variety of forms. Sometimes servants were spoils of war. That is certainly unlikely in the case of Eliezer. Sometimes servants were acquired economically. They could be sold to the “master.” They might even sell themselves to their master in order to eradicate some debt. Or they might, in some cases, just hire on. The Hebrew word for servant or slave is a fairly broad term. Somehow, Eliezer became a servant to Abram. It might have happened after the migration, but what would an unattached Aramean be doing in Canaan?

So, we conclude that sometime before Abram’s migration to Canaan, this man Eliezer became one of his servants. As we shall see, over some period of time, Eliezer became a servant with significant responsibilities. He proved his worth to a very high level of trust.

We don’t know how many animals or servants Abram brought with him when he moved to Canaan. We do know that he became quite wealthy over time. Even in the context of his strange journey to Egypt, he was enriched. Over time, as things worked out well for him and his camp, many servants would come to be in his employ. By the time he decided to engage in the rescue mission on Lot’s behalf, he was able to put a small, trained army in the field. He probably did that without even risking those who stayed behind. Again, we cannot be completely sure, but it is likely that the larger portion of his group of servants had come under his care after the arrival in Canaan.

Eliezer, then, would be one of the servants that was with Abram longest. Perhaps this influenced the trust Abram placed in him. Of course, Abram, like any other group leader, would be interested in finding real talent and loyalty where he could among his servants. It makes sense to invest trust in the trustworthy. The relative ranks of the servants would likely be determined by capability and trustworthiness in addition to longevity. In fact, longevity might have been a lesser reason. For now, let’s assume it was some combination of capability and trustworthiness that Abram saw in Eliezer. Those things would complement his longer acquaintance.

Obviously, Abram did come to think highly of Eliezer. Some number of years after he moved to Canaan, Abram was complaining to the Lord one day. In his complaint, he stated specifically that he despaired of ever producing an heir. To stress the point with God, he complained that the absence of a son would lead him to pass his estate on to Eliezer of Damascus (Genesis 15:1-3). Why not some other servant? The answer seems to be that of all the servants in the camp, Eliezer was the one most qualified (in Abram’s opinion) to keep the estate together after Abram’s death. While it is true that Abram was complaining, it is also true that he revealed that Eliezer was the servant he would most trust.

This was no light matter. If Abram were to die before his wife Sarai, whoever was left with the estate would be the man who was responsible for her welfare from that time. Abram would have given much thought to that issue. He wanted a son, but in the absence of one, he was willing (at that time) to entrust the wellbeing of his beloved wife to this servant, Eliezer of Damascus. Surely this implies that Eliezer was the “highest-ranking” servant in the entire camp. At least, he had achieved the status of “most-trusted.” That would not be a matter of longevity only. It had to be trust, whatever else might be involved.

We might even go so far as to suggest there was some form of love involved in the relationship between the two men. It is not hard to imagine that after long years together the two were close friends, in spite of the employment arrangement. Abram likely found himself consulting with Eliezer in matters that affected the welfare of the entire camp. There may well have been cases when the advice Abram received from Eliezer was followed to the gain of all.

It is not a far fetch to suggest that Abram and Eliezer even shared the idea that the latter could become the leader of the camp in the event of Abram’s death. After all, there was no other obvious person to run things. One is tempted to think that Abram would need to make his wishes clear to the folks concerning who was the person to take over so that things would not be left to chance. Because all the men in the camp except Abram were servants (Canaanite or otherwise), his death could result in very unfortunate consequences in addition to the dissolution of the camp. In short, it was probably already known that Eliezer was the designee.

We wonder whether Eliezer was disappointed at the birth of Ishmael (Genesis 16:15-16). At that point in time, it became unreasonable to maintain any expectation that he would ever be the leader: Ishmael would be the designee. Eliezer was probably very involved in the training of Ishmael. If so, he must have performed well. We might see the light of nobility in the man who was a trusted servant.

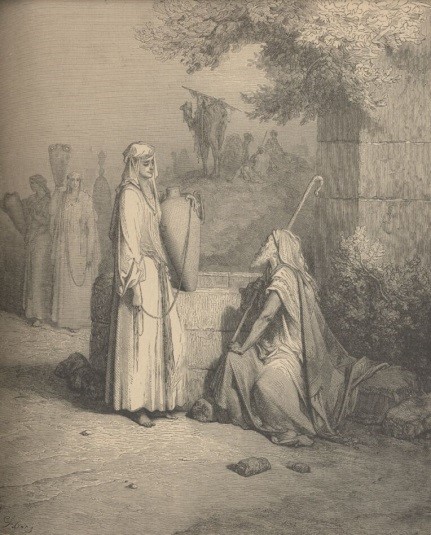

About fifty-five years after Ishmael’s birth, Isaac was approaching his fortieth year (Genesis 24:1-32). We do not know whether Eliezer was still alive at that time, but let’s assume he was. What we do know is that Abraham sent for a particular servant. The Hebrew suggests the servant was an “older” servant. The servant was to be entrusted with a most sacred mission. The woman whose womb was to bear the third generation of the “great nation” needed to be found. A very special vow was to be made by the servant. Try to imagine the gravity of the moment. This was a pivotal moment in sacred history. In that moment Abraham was to entrust this ultimate task to a servant – probably the servant who might have been the “heir” himself. He was to be given very rich gifts to provide as a bride price. He probably even had to go near the place of his birth along the way. Damascus was not directly on the route but would not be far off the route. Was he tempted to return to the place of his nativity and keep the gifts? That would make him a rich man. That is not what he did.

When he arrived at his destination, he prayed to the God of his master that his mission would be perfectly fulfilled (Genesis 24:12-14). It was.

The MAN FROM DAMASCUS fully rewarded the loving trust of his master.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.